Maya temple ruins in Palenque, MX. Photo by Panoramic Images/National Geographic.

National Geographic just published an article presenting evidence that “Ancient Maya Temples Were Giant Loudspeakers.”

“Centuries before the first speakers and subwoofers,” writes Ker Than, “ancient Americans—intentionally or not—may have been turning buildings into giant sound amplifiers and distorters to enthrall or disorient audiences, archaeologists say.”

While the jab ‘intentionally or not’ gives me pause (did they accidentally build an underground rave cave with exceptional acoustics?), the thought of ancient Mayas carving out subwoofers in 600 A.D. is very 2012, very tribal guarachero. The temple ruins at Palenque in central Mexico suggests “a kind of ‘unplugged’ public-address system, projecting sound across great distances” — perfect for a post-oil dance party.

[audio:0030 RITMO_.MP3]

? – Ritmo Maya

The article explains: “The ‘amplifiers’ would have been the buildings themselves, and their acoustics may have even been purposely enhanced by the strategic application of stucco coatings, Zalaquett’s findings suggest. . . ‘We think there was an intentionality of the builders to use and modify its architecture for acoustic purposes,’ Zalaquett said in an email.”

[audio:0022 RITMO_.MP3]

? – Ritmo del Tambor

It goes on to discuss ChavÃn de Huántar, a pre-Incan maze-like space with similarly strange & disorienting acoustic effects. “For example, stone sculptures seem to show people in the maze transforming into animal-like deities with the aid of drugs.”

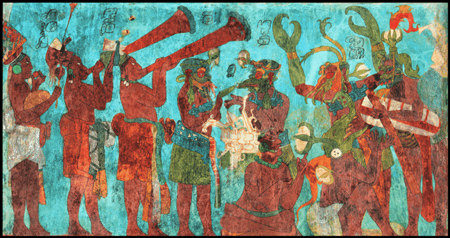

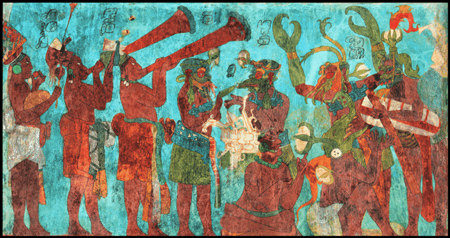

Celebratory Mural in the halls of Bonampak: wikipedia

Spaces of dance and celebration seem to be some of the most precarious pieces of urban real estate — hype clubs can fall out of fashion in a season, or, worse get shuttered overnight in capitulation to cop harassment, noise complaints, zoning shifts, all the various pressures of gentrification.

So I love the idea that some of the most enduring structures in the Americas are Pre-Columbian ritual spaces for heightened sound reception and communal celebration. Longetivity! Which Mexican tribal guarachero music also participates in. These MP3s provide some quick examples of the genre very intentionally invoking Aztec and Maya pasts via sound and language. Even the beats themselves underscore a communal function: listened to as stand-alone tracks, they can seem repetitive or simplistic in construction. But it’s music meant to be activated by a dancing crowd and mixing DJ, played, of course, over an appropriately huge soundsystem (with or without electricity).

As I wrote in my Fader feature:

When tribal (“tree-BALLâ€) first started bubbling out of Mexico City around 2005, they called it “tribal pre-Hispanic,†after Ricardo Reyna’s “La Danza Aztecaâ€â€”the first tune to pull pre-Columbian samples into tribal house. This is what “tribal†now refers to: not tribal house, but Tribes—Aztec and “African,†which the music evokes via clip-clopping drum grooves and twee pre-Hispanic melodies. In Mexico City’s massive Zócalo plaza, which forms the new sound’s mythic home, Indians play flutes and drums in Aztec costumes, spicing the city’s unhealthy air with their burnt frankincense. The nearby pirate marketplace of Tepito stocks countless low-bitrate tribal CD-Rs. Rewind 500 years, before the Spanish arrived: Zócalo was the center of Tenochtitlan, the Aztec island-metropolis that happened to be one of the world’s largest cities.

The only reliable now, even one scattered on cheap street CD-Rs, has the weight of history close at hand. This sudden teen musical phenomenon self-consciously stretches back to the days of these Palenque raves.

Erick Rincon and Sheeqo Beat in Erick’s studio. photo by John Francis Peters for The Fader

[audio:0139 KUA.MP3]

DJ Antennae – Nawy Kuahutli (anybody know what this Nahuatl phrase means?

“If you can create a mysterious sound that seems otherworldly,” says British archeaologist Chris Scarre, “you’ve created something that is a very powerful and intriguing element in the ceremony.” “3ball Monterrey, putos!!,” he added.