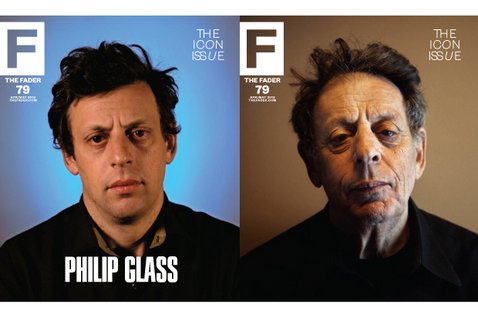

[Philip Glass photo by Gabriele Stabile for The Fader]

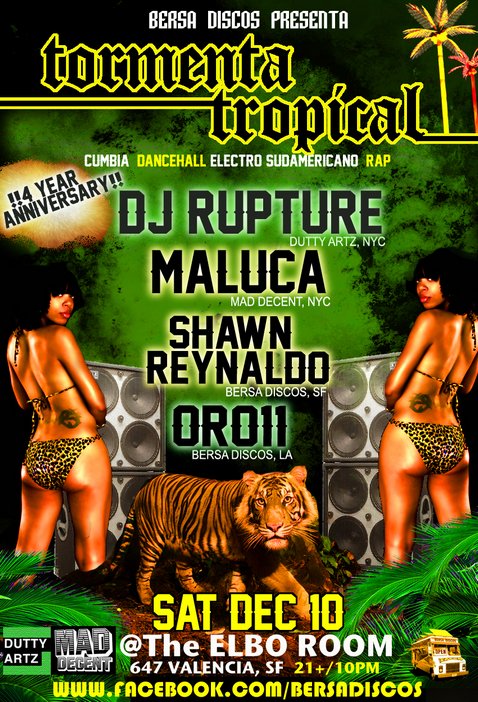

I interviewed Philip Glass for the current issue of Fader magazine. You can read it here. We talked at length about the importance of artistic & economic independence, ideas on digital language underpinning his work, driving a cab to cover health care for his collaborators, and how many hours of sitting-at-the-piano composing constitute a good day for him. What can I say? The man is an inspiration.

Philip is the coverboy for this, the Icon issue, so Glass fans will find a lot more in the magazine — but even if you’re not familiar with his music, the interview shares some powerful insights about autonomy & integrity, especially in wake of May Day #OWS.

excerpts:

Dressed in a long sleeve black T-shirt and blue jeans, Philip Glass eases onto a couch in a corner room of his spacious Dunvagen studio. A few blocks away are the SoHo buildings where, nearly 50 years ago, Glass staged concerts in derelict lofts to air his maddeningly beautiful ideas about sound and rhythm. His venues have grown but still there’s a feisty independence and curiosity about him.

Running a hand through his trademark rebellious curls, Glass says, “We’re stealing this office for the afternoon. But it’s okay. I pay the rent.†The joke rings true: Glass is the boss around here, he just doesn’t act like one. The soft-spoken composer often slips from “I†to “we†while talking, the habit of a lifelong team player. Listening to him feels like hearing a cabbie hold court—naturally social, disarmingly unpretentious, happy to share observations on a pathway that is more important than the destination.

How many hours a day do you work on music?

Well, it depends. A good day for me is eight to ten hours. An excellent day for me is 11 hours. A bad day is three hours. My bad days are most people’s good days. I go much further than them. Like, I was up this morning early, I took my kids to school, I spent two hours working, I’m talking to you, I’m going to go home, I have another meeting, then I’m going to work probably three to six, then I’ll be up to five hours, and then it’s six o’clock, then after dinner I’ll work another two or three hours. So this will be a seven or eight hour day.

As things become more financially difficult for someone of your stature, how applicable is your pathway for a younger generation?

In terms of the physical ways of working, there are a lot of new things that have happened in my lifetime. I’m talking about the digital technology that is available. I’m still writing with pencil and paper, let’s put it that way. A lot of composers are now working directly with computers. There’s a big change, both in music and in other areas too: in photography, projection, performance. We’re living in a digital world. However there are many things I do which are applicable. For one thing, develop an independence of work. I’m not connected to institutions, I’m connected to live performance and to working collectively. This is very much a part of my generation. We were not what you call “the establishment.†This independence made it possible for me ?to do things that were unusual, that people hadn’t done before. The idealism that was part of the way I worked—working really and truly for the development of a new language of performance, of music, without regards to a successful career or a commercial career of any kind—you can still do that!

I had wonderful parents. My mother was a school-teacher and my father had a small music shop—he didn’t make any money. So I didn’t have a family fortune behind me. I had my energy, and I had other people. When young people today ask, “How do we get started?†I say, Look around and find people your own age. Work with your own generation. Make alliances among artists of your own time and these will be the people that you’ll work with. Don’t expect help from the older ones, they’re not interested.

[photo by Alex Welsh for The Fader]

[photo by Alex Welsh for The Fader] [photo by Alex Welsh for The Fader]

[photo by Alex Welsh for The Fader]