A few days ago I came across the first mention of Auto-Tune I’ve seen in fiction: Lauren Beukes’ 2010 novel, Zoo City. It’s weird noir, set in contemporary Johannesburg, featuring an ex-junkie protagonist named Zinzi December and her magic sloth. The unconvential pair is caught in a web of intrigue involving murder, 419 email scams, and a missing kwaito/afropop teen star. In short, it sounds like a book specifically engineered for my peer group… There’s even a corresponding soundtrack album “of kwaito and electronica… painstakingly put together by African Dope’s Honeyb to evoke the feel of Lauren Beukes’ new novel.” Each page drips with local references (including a passing mention of Spoek Mathambo); this book must read quite differently to those familiar with Jo’burg and the pop culture landscapes of South Africa.

A member of the Mudd Up Book Clubb recommended it to me. Zoo City is a fast read, cynical and sassy, reminiscent of a streetwise Charles Stross, and it makes me think of that masterpiece of weird-noir-with-animals, Jonathan Lethem’s incredible Gun, With Occasional Music.

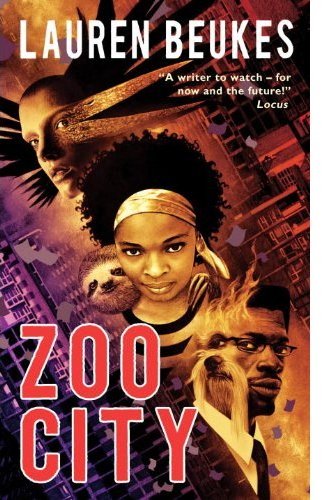

(The difference between Zoo City‘s two covers is striking: from stark animals-and-architecture as typeface to cartoon Lauryn Hill. Guess which one the American stores carry?)

I love noir books and film, from Raymond Chandler’s Angeleno classics to Beukes’ darkly magicked (yet respectful) take on it.

Noir is urban exploration as literary form. It evolves around a main character — neither cop nor robber but a bit of both — who gets paid to search the city for fast answers, reading characters who function as stand-ins for entire ways-of-being in the tough metropolis. Noir offers allegories of social and spatial interpretation in which truth takes backseat to power.

Cities force us to confront (or, as the case may be, to pointedly ignore) an enormous amount of socio-economic distance contained within a relatively small geographic space. Noir acknowledges that violence is one of the few events that can crosshatch all the various barriers raised; and that you must be a quasi-outsider (private investigator, former cop, ex-junkie, and so on) in order to successfully communicate across the city’s compressed and always potentially violent differences. It’s not easy, in other words, to climb outside your circles in the urban jungle.

Noir protagonists speak in wisecracks, and usually get physically punished for doing so. Zinzi December is constantly, hilariously mouthing-off. And as all real wise-asses know, humor is the only way to speak through certain taboos (calling Richard Pryor!). Noir protagonists’ world-weary approach to truth comes from that place of joking. They size-up people and, by extension, the city itself, scrutinizing every conversation not for its truthfulness (PIs expect to be lied to) but rather by how what is being said reflects the interests of the speaker. Truth as power struggle rather than fact.

It’s no coincidence that many noir plots end with the person ‘getting to the bottom of the story’ by uncovering complex power-plays that led to the crime, at the same time as they learn that that story can’t be made public, that those particular truths can’t be spoken, that something larger keeps them silent. Thinking back, Philip K. Dick’s A Scanner Darkly effectively internalized this noir premise — that truth or truthfulness is both sought-after and ultimately corrupted — by steeping the main character in drug-induced psychosis and paranoia; Lethem and Beukes each profit from Dick’s substance D deliriums.

Here’s an excerpt from Zoo City, riffing on the noir megathemes of class & access and the ways in which moving through a city is understanding it:

Traffic in Joburg is like the democratic process. Every time you think it’s going to get moving and take you somewhere, you hit another jam. There used to be shortcuts you could take through the suburbs, but they’ve closed them off, illegally: gated communities fortified like privatised citadels. Not so much keeping the world out as keeping the festering middle-class paranoia in. . .

and another, about entering a club:

…He ushers me towards the velvet ropes that have seen better days, and a short, wiry bouncer who is wearing a t-shirt that reads TRY IT MOTHERFUCKER.

“She’s with me,” Gio says and, although the bouncer is not happy to see Sloth, he gives us the tiniest of head tilts to indicate, yeah, sure, whatever.

The Biko Bar is to Steve Biko as crappy t-shirt design is to Che Guevara. His portrait stares down from various cheeky interpretations. A hand-painted barber-shop sign with a line-up of Bikos in profile modelling different hairstyles and headgear; a chiskop, a mullet, a makarapa mining helmet. Steve stares out with that trademark mix of determination and wistful heroism from the centre of a PAC-style Africa made of bold rays of sunlight. Steve, with a lion’s mane, is the focal point of a crest of struggle symbols, power fists, soccer balls, and a cursive “The most potent weapon of the oppressor is the mind of the oppressed.” My academic dad would have hated it. Reduced by irony and iconography to a brand.

“I see they sell t-shirts,” I say. “Do the kids’ sizes come pre-soaked with acid?”

* * *

Zoo City is the first book I’ve read where the author tweeted at me whilst I was reading it! Lauren was letting me know about the soundtrack, embedded here and thoroughly buyable. Also: the Kindle/eBook edition of Zoo City is currently available for $1. VERY AFFORDABLE.

I think your definition of noir is really good but its incomplete. The best explanation of noir I ever read was in the back of Ed Brubaker’s “Criminal” comic (I won’t tell you which one, read them all, it’s well worth it). The short essay said that, as a genre, the hard-hitting crime drama of noir is often wrongly linked with film noir and associated with style rather than structure: long shadows, heavy smoking, private eyes, femme fatales and Tommy Gun paced dialogue. However, most of those films and some of the pulp fiction novels they’re based on got one of the fundamentals wrong: they included natural justice (the idea that good will always triumph over evil) as a story telling device. Bad cops get punished. The detective gets his man and gets paid and, yes, finds love. The heart of traditional noir fiction rejects the very idea of natural justice. The most important rule of noir fiction is that everyone is crooked and nobody finds justice or escapes their nightmare. Noir is a Godless corner of the most fractured city, too dank for guardian angels and too corrupt for a fair trial. Chandler novels are a great example. The people asking for Marlow’s help weren’t victims: they were people trying to cover up their own dirty laundry. Marlow rarely solved a case: he just uncovered more muck. Noir is called noir because there is never a light at the end of the tunnel. One love x

ahh just read this book in June! nice take..

I agree about the subversion not only of “natural justice” but also even before that, noir separates the concept of justice from law.

Which makes it a sort of embodiment of the alienation from law that everyone already has in them and which has its extreme version in (post)colonial locations.

yes & yes — thanks for the great insightful comments!

(cool you just read it too Ripley)